SPIRITUALS

OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN FREEDOM STRUGGLE:

BUILDING

COMMUNITY AND ORGANIZING PROTEST

A

THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF

THE

MASTER OF LIBERAL ARTS PROGRAM OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY

IN

PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL ARTS

Marianne

Mueller

June

2012

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Clayborne Carson, who first told me parts of

this story, taught me the outlines of this history, and encouraged and inspired

me to explore the music of the civil rights movement to investigate how it

affected historic achievements of the 1960s.

Table of Contents

Introduction………………………………………………………......................................1

Chapter

1: Exodus—“Go Down, Moses” and “Go Tell It on the Mountain”……….….....4

Chapter

2: Perseverance—“We Shall Not Be Moved”…………………..........................35

Chapter

3: Freedom—“Oh Freedom”………………………............................................48

Chapter

4: Community—“We Shall Overcome”…………………………………...........66

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….....99

Bibliography……………………………………………................................................104

Introduction

Freedom songs played a critical role in

the civil rights movements of the sixties. Less known is their importance to

the African American struggle for freedom over the past two hundred and fifty

years. Two factors account for the power of music in the struggle: the

emotional effects of the music, and the songs’ suitability for grassroots

organizing.

Spirituals composed between 1750 and

1850, and their musical descendants, comprise the greater part of this body of

music, although protestors also adapted secular folk songs, modified

contemporaneous popular songs, and composed new songs. Spirituals proved more

effective than secular songs as protest music, and their music

and rhythm gave later freedom songs their power and influence.

Narratives of the African American

struggles for freedom follow the work of formal organizations and their

leaders. But grassroots culture and bottom-up leadership sustained the civil

rights movement and the struggle against slavery that preceded it. Freedom

songs brought disparate communities together, and sustained and energized the

movement. They expressed shared commitment, strengthened perseverance, and

sometimes healed the divisions that arose after arguments among activists.

According to one authority, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

was effective despite its apparently leaderless structure and egalitarian

principles because

songleading

fostered a kind of organic and tacit leadership necessary to conduct the

day-to-day affairs of the movement. Songleading functioned as a de facto

authority from which other responsibilities tended to flow. It is not

coincidental that some of the most prominent individuals in the history of the

civil rights movement, including Fannie Lou Hamer, James Farmer, Cordell

Reagon, and Bernice Reagon, were songleaders.[1]

The themes

exodus, freedom, perseverance,

and community infuse spirituals and

their musical descendants, the protest songs or freedom songs. Each chapter in

this thesis focuses on a spiritual that exemplifies one of these themes. The

first chapter traces the history and influence of “Go Down, Moses.” This

nineteenth-century spiritual of exodus links directly to the civil rights era

freedom song, “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” Influential songleaders Harriet Tubman (associated with “Go

Down, Moses”) and Fannie Lou Hamer (strongly identified with “Go Tell It on the

Mountain”) led grassroots communities in the African American freedom struggle.

Harriet Tubman led slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad, and was

popularly known as Black Moses. Fannie Lou Hamer led protesters in the twentieth-century

struggle against Jim Crow. Although people did not give Hamer the name “Moses,”

she led communities in singing the exodus-themed spiritual “Go Tell It on the

Mountain,” and like Moses of the biblical exodus, led people in the struggle

against Jim Crow.

The somber

nineteenth-century spiritual “No More Mourning” evolved into the joyous and

celebratory “Oh Freedom.” This thesis postulates that the African American

freedom struggle evolved analogously. Myles Horton of the Highlander Folk

School learned “No More Mourning” from an organizer of the Southern Tenant Farmers’

Union in the late 1930s and brought it back to Highlander. Zilphia Horton,

Highlander’s music director, wove it into the body of protest songs she taught

for decades across the south during the labor movement, and it figured as one

of the most prominent freedom songs of the sixties. “Oh Freedom” links songleaders

and organizers John Handcox, Zilphia Horton, Joe Glazer, Guy Carawan, Bernice

Reagon, and dozens more, all of whom used the freedom songs deliberately to organize

resistance at the grassroots level. Despite its original sorrowful tune and

lyrics, once transformed, “Oh Freedom” became a paradigmatic song of freedom,

in addition to revealing links among protest movements and their grassroots

leaders.

“We Shall

Not Be Moved” and “We Shall Overcome,” two spirituals used as protest songs,

helped protesters persevere and come together as a community. They became

anthems: “We Shall Not Be Moved” in the labor movement and “We Shall Overcome”

in the civil rights movements. They reveal significant connections among songleaders

of different generations and locales. Both anthems bridge the labor movement

and civil rights movement, linking the grassroots organizations Highlander Folk

School and SNCC. They connect songleaders and singers, famously Zilphia Horton

and Guy Carawan, but also traditional folk communities and communities of Northerners,

whites, secular African American students, and others who heard freedom songs

for the first time during the civil rights movement.

These four

prominent, influential, and long-lasting spirituals, among the hundreds used in

protests, crystallize themes that permeate struggles. For example, exuberance

and victory, the themes of “Of Freedom,” underscore that spirituals’ themes

ranged the spectrum of emotion, not limited to the wails heard in the sorrow

songs analyzed by W.E.B Du Bois.

The

intrinsic power of spirituals’ music explains their influence in protest

movements. Yet without the organizing efforts of grassroots leaders, the

spirituals could not have been as effective as history shows. These two

factors—the power of the music, and their deliberate use by grassroots

organizers—account for their success.

Chapter 1: Exodus—“Go Down, Moses” and “Go Tell It on

the Mountain”

“Go Down, Moses” and “Go Tell It on the Mountain” show links

among grassroots songleaders and organizers in the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries. These two songs taken together provide one example how folk

spirituals emerged and gradually transformed into the freedom songs sung in civil

rights protests in the sixties. The story begins organically among slaves on

the plantation, on the Underground Railroad, and in the contraband camps of the

Civil War.[2]

Slaves, escaping slaves, and freed slaves sang “Go Down, Moses” in camps and

before British royalty. Members of the Union Army, northern politicians, and

northern society at large heard “Go Down, Moses,” and the spiritual reached large

white audiences in the United States and in Europe. Later, during the civil

rights movement, the songleader and activist Fannie Lou Hamer picked up its

theme (exodus) and main lyric

(“Let my people go”), and transformed the Christmas hymn “Go Tell It on

the Mountain” into a song of exodus. Singers in the sixties kept intact the

melody, rhythm, and tempo of “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” but completely

rewrote the narrative and lyrics, centered on the key phrase from “Go Down,

Moses”—“Let my people go.”

“Go Down, Moses” and “Go Tell It on the Mountain”

remain widely sung in black and white churches, but “Go Tell It on the Mountain”

is remembered primarily as a civil rights protest song with the introduced exodus

lyric, “Let my people go.”

“Go Down, Moses”: Theme

Exodus resonated with African Americans during

slavery, during Reconstruction, and during Jim Crow. While Christianization of

slaves’ native religions took place gradually, by the mid-eighteenth century,

African Americans across the South knew the biblical version of exodus. Scores

of exodus spirituals arose in the days of slavery. Moses, God’s chosen people,

Pharaoh, the Red Sea, wandering in the wilderness, and arriving at the promised

land form the themes of dozens of spirituals. In addition to “Go Down, Moses,”

the songs “Didn't Ole Pharaoh Get Lost in the Red Sea,” “The Ole Ship of Zion,”

“When Moses Smote The Water,” “Brother Moses Gone,” “O Mary Don't You Weep, ‘Cause

Pharaoh's Army Got Drownded,” “Turn Back Pharaoh's Army,” “I Am Bound for the

Promised Land,” “Way Down in Egypt Land,” and “O Walk Together Children” describe

the biblical exodus specifically, and, using code, describe the African American

exodus from slavery. These spirituals, among many others, established and

spread the coded language used among enslaved peoples to express their

conditions and to plan and carry out escape.

The theme of exodus ran like a

subterranean river beneath all other themes, expressing the hope of slaves for

a journey out of slavery (and later, sharecropping and Jim Crow). Enslaved

peoples did not wait for white society to deliver them to freedom. Rather, their

freedom resulted from journeying through the wilderness, overcoming seemingly

insurmountable obstacles, following community leaders, and—as they

described it—through grace and prayer reaching the promised land. All

songs of resistance take shape around this central theme of exodus.

A large collection of specific themes and

images derive from the general theme of exodus, the biblical story of the mass

departure of Israelites from Egypt. Exodus signifies the literal journey from

slavery into freedom, and identification with God’s chosen people, and describes a powerful, charismatic leader

chosen, blessed and commanded by God to bring His chosen people to freedom. It articulates

resistance against oppressors: Pharaoh and Pharaoh’s army in the biblical

version, slaveholders and the Confederate Army in the mid-nineteenth century. The

strength of exodus as a rallying call relies on a shared belief in the sure and

safe deliverance to the promised land: Canaan under Moses, and Canada or the North

under Harriet Tubman. Like the Israelites in Exodus, community and perseverance

brought African American slaves to the promised land, not the efforts of liberators

associated with formal abolitionist movements, although freedom did not arrive

without the added efforts of abolitionists.

Roots of Spirituals

Some historians and musicologists of the

nineteenth century held that spirituals expressed slaves’ resignation to their

fate, and their hope for deliverance after death, not in life. Even scholars

writing in the mid-twentieth century considered spirituals a religious balm

only—pious traditions that helped slaves endure until their only form of

salvation arrived, their own deaths. Scholars interpreted spirituals as prayers

for deliverance by Jesus, and a yearning to unite with God in heaven to find

peace and rest. This attitude dovetailed with the notion that slaves submitted

to slavery, were not able to organize resistance, or found slavery not

intolerable. Views that rationalized slavery led to a sociology where African Americans

were considered childlike, simple, meek, willing to submit, without agency, and

unable to demand freedom and act on that demand. Even sympathetic collectors of

African American folk song, more aware than most of the history and conditions

of slavery and its coded music, wrote disclaimers like the following:

In his songs, I

find him, as I have found him elsewhere, a most naēve and unanalytical-minded

person, with a sensuous joy in his religion; thoughtless, careless, unidealistic,

rather fond of boasting, predominantly cheerful, but able to derive

considerable pleasure from a grouch; occasionally suspicious, charitably

inclined towards the white man, and capable of a gorgeously humorous view of

anything, particularly himself.[3]

The music and lyrics of the spirituals, and the history of

peoples who sang them and used them in resistance, show otherwise. African

American music pervades the centuries-long struggle for freedom. Spirituals

supplied narratives of the journeys, and served as coded protest songs. More

than metaphor or emotional release, African American music literally traces the

journey to freedom, and the path of non-violent resistance practiced for

centuries.

Scores of early spirituals explicitly invoke images of death,

but slaves understood references to death as references to deliverance from earthly

enslavement. Spirituals like the antebellum “From Every Graveyard” can be read

literally, as the community of brothers uniting after the Christian

resurrection:

Just behold that number

From every graveyard

Going to meet the brothers there

That used to join in prayer

Going up thro’ great tribulation

From every graveyard.

Many spirituals paint an image of the singer joining the

community that went before, and that now dwells in peace and joy in heaven. Death

is postulated as the alternative to slavery: “Before I’ll be a slave/I’ll be

buried in my grave.” However, the earthly, immediate alternative to the daily

reality of slavery was freedom, not death. From their inception, spirituals communicated

codes, as well as purely religious sentiments. Slaves endangered themselves,

their families, and their communities when singing openly of freedom. In this

verse from an eighteenth-century secular song, a slave explains that his

singing covers up his true feelings and intentions:

Got one mind for white folks to see,

‘Nother for what I know is me;

He don’t know, he don’t know my mind,

When he see me laughing

Laughing just to keep from crying.[4]

Spirituals that on the surface refer to death as deliverance

contain codes referring to freedom. Singing about joining those who went before,

or about wishing to reach the promised land, did not represent turning away

from this life, but a desire to join freedmen escaped from slavery.

Spirituals’ stories, themes, and images

trace to African cultural norms and religious expression. African rhythms, polyrhythms,

the distinctive call-and-response form, and other aspects of African music manifest

in music of spirituals. When Northerners first learned spirituals in the

post-Emancipation era, prominent music dictionaries described Negro spirituals

as musically and lyrically derivative of the white church hymns that slaves

heard in the early nineteenth century.[5]

Collectors and musicians who listened closely to spirituals strenuously

objected, since the music and form of slave spirituals differed enormously from

white church music. Nevertheless, this view was not put to rest until the mid-twentieth

century. While white and black church music influenced the other, the enslaved

African American community created new musical features not found in other

American or African music. They introduced these elements into the broader

strains of American music, enriching the latter, and creating wholly new genres

of music: spirituals, gospel, ragtime, blues, jazz, rhythm and blues, rock and

roll, rock, funk, hip hop, rap, and more. African American interpreters

re-assembled some white spirituals from the early nineteenth century, but the

result was new and unique, not an imitation.

Music translated everyday experiences and

religious practices into living sound in West Africa during the time of the

slave trade. John S. Mbiti wrote a comparative and interpretative study of

African religion based on the beliefs, elements, and characteristics of more

than three thousand African ethnic groups, each with its own religious system.

Despite the diversity of religious beliefs that conform to local societies, and

the wide range of linguistic groupings, fundamental concepts, ritual, and

cultural expression are common across African religions. African religions

practiced by slaves contained notions complementary to Christian descriptions

of God, the role of God, and the relationship between God and man:

In all African societies, without a

single exception, people have a notion of God—a minimal and fundamental

idea about God. Like the Christian God, the African God is known as a High God,

a Supreme God, a father, king, lord, master, judge, or ruler, depending on the

society doing the naming (or, in some matriarchal societies, Mother, although

the image of God as Father is not limited to patriarchal societies). God is a

Creator and Provider who reigns in the sky or heaven and over heaven and earth,

the two having originally been either close together or joined by a rope or

bridge. Africans are expected to be humble before him, to respect and honor

him. This image of God is the only image known in traditional African societies.[6]

Native African religious beliefs readily

incorporated Christian theology. Christianity explained God’s role differently,

and provided new rituals, but did not supplant traditional beliefs and rituals.

Slave masters held conflicting and contradictory views of this syncretism, over

time, and in different locales. Some slaveholders found slave religion

threatening, and liable to incite insurrection or present slaves with dangerous

notions of equality before God and man. They consequently forbade the practice

of religion of any type. Others found the New Testament admonitions of Paul for

slaves to be obedient to their masters a useful tool. Christianity became the

dominant overt slave religion, firmly in place by the mid-eighteenth century. The

practices of African diasporic religions, blended with Christian rituals,

continue today. Christianity supplemented and enhanced religious expressions in

early African American culture; it did not replace them. As in Europe, where

Christianity absorbed indigenous religious rites, the practice of Christian

religion among slaves absorbed prior practices of African religions. Significantly,

music remained central to African American religion and daily life.

African American slaves’ embrace of

prophets and saints in spirituals and rituals also parallels traditional

African religions. Daniel, Joshua, Moses, Peter, Paul, and dozens of Old and

New Testament figures that appear in slave song are analogs of African

“mythological figures of a spiritual nature.”[7]

These lesser Gods, or intermediaries, acted as diviners of wisdom, divine

hunters, or tricksters, who helped and interfered with daily life.

The presence of music in all spheres of daily

life persisted as the most important aspect of African culture brought to

America. African Americans under slavery, like their ancestors in Africa, drew

no formal distinction between the sacred and profane, the spiritual and

material. Most linguistic groupings in African cultures contained no specific

word for religion; religion infused all aspects of life. Rhythmic expressions

predominated. Music and dance were synonymous with religious expression, and part

of worship and daily work. Harvesting, hunting, education, politics, homemaking,

and community life centered on music created and performed not by individuals,

but communally. Likewise, music permeated all aspects of life in slave society.

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century letters, essays, and histories documented the

prevalence of music among slaves. Slaves across the South, and in all regions

where slavery was practiced, wove rhythmical expressions (using the body or

instruments), moans and chants, ring shouts, songs, and dances—practiced

individually and communally—into work and communal activities, play, and love.

Slaves enduring suffering, violence, forced family separation, and imprisonment

relied on music to relate their stories, and gain strength to persevere. Slaves

deliberately separated by linguistic groupings to prevent conspiracy to rebel

employed music as a universal language, and formed inter-linguistic

communities.

Spirituals share a traditional

understanding of death and the dead with African religious traditions. The dead,

in African cultures, inhabit the spiritual world along with God and the “lesser

Gods,” or intermediaries; the dead migrate to the spiritual realm, but do not

cease to exist. This parallels the Christian belief in life after death, except

that in African traditions, the dead remain an active part of the community as

long as they are remembered. Even after the memory of an ancestor fades

completely, the person is not considered dead in the sense of not existing, but

simply in the state of an ordinary spirit not known by name. The dead are

literally the living dead, reincarnated in the spiritual realm. The Sengalese

poet Birago Diop writes:

Those who are dead are never gone

They are in the brightening shadow

And in the thickening Gloom

The dead are not beneath the Earth

They are in the quivering Tree

They are in the groaning Wood

They are in the flowing Water

And in the still Water

They are in the Hut,

They are in the Crowd;

The Dead are not Dead.[8]

Unique syncopated and multi-meter rhythms,

melodies in a pentatonic “blues scale” that created sorrowful and joyful

tonalities, improvised lyrics, ring shouts, and ecstatic dance combined to form

spirituals based either on universal religious themes or Old and New Testament

stories. Lyrical and musical analyses of

each spiritual discussed in this thesis describe characteristics of the spirituals’

rhythms, tonalities, and improvisations.

Go Down, Moses: Lyrical

Analysis

Exodus 8:01 and subsequent verses of the

chapter of Exodus in the Old Testament inspired “Go Down, Moses”:

And the Lord spoke unto Moses, go unto

Pharaoh, and say unto him, thus saith the Lord, Let my people go, that they may

serve me.

“Go Down, Moses” traces the story of

Exodus in thirty-six verses. This chorus follows each verse:

Chorus

Go Down, Moses

Way down in Egypt land

Tell ole’ Pharaoh

Let my people go.

Each verse contains an image taken from

the biblical exodus, including “I’ll smite your first-born dead,” “Stretch out

your rod and come across,” “The cloud shall cleave the way,” “Pharaoh and his host

were lost,” and “Let us all to Canaan go.” Two call-and-response couplets comprise

each verse:

Verse 1

When Israel was in Egypt’s land, [Call]

Let my people go, [Response]

Oppress’d so hard they could not

stand, [Call]

Let my people go. [Response]

Chorus

Go Down, Moses,

Way down in Egypt land,

Tell ole’ Pharaoh,

Let my people go. [Resolution

of Chorus[9]]

The third line, “Oppress’d so hard they

could not stand,” continues the narrative begun with the first line, “When

Israel was in Egypt’s land.” Each verse follows the same pattern: a call, followed

by the response “Let my people go,” and a second call, followed by the same

response. A congregation responded “Let my people go” seventy-two times over

the course of singing all thirty-six verses. “Let my people go” also culminates

the chorus that follows each verse, so that a congregation responded “Let my

people go” over a hundred times when singing “Go Down, Moses.” “Let my people

go” is the idea and image that rolls through the spiritual, binding verse to

verse, and culminating in each repetition of the chorus. The phrase “Let my

people go” hangs in the air after the song is done. “Go Down, Moses” demands freedom, unyieldingly.

Calls arose from different people in a congregation,

which then responded together “Let my people go.” A narrative built gradually,

different people adding lines to the lengthening collection of verses. Over

time, the congregation settled on standard verses, and participants sang mainly

the known calls and responses—that is, sometimes people did not add many new

verses, if any at all. But usually, during any one recitation, members of the

congregation added new verses. Visitors who transcribed music and lyrics

captured an incomplete set of verses, only the verses they happened to hear at

a church or camp.

Several verses of “Go Down, Moses” introduced New

Testament stories to the narrative, as well as aspects of nineteenth-century African

American daily life. “O let us all from bondage flee/And let us all in Christ

be free” incorporated Christ of the New Testament with the Exodus story. “I’ll

tell you what I likes the best/It is the shouting Methodists” and “I do believe

without a doubt/A Christian has a right to shout” cast light on how African

American culture integrated with Christian church culture. “Shout” refers to a

religious dance. People gathered in a small wooden church shuffled slowly in a ring,

chanting and singing, pounding out rhythm with percussive instruments. Ankles never

crossed, as happened in a “Devil’s dance.” The ring shout would not be

understood or embraced by white churches, and African Americans felt more at

home with “the shouting Methodists,” who agreed “a Christian has a right to

shout.”

Some of the original verses of “Go Down,

Moses” explicitly address conditions of slavery. The verses “We need not always

weep and moan/And wear these slavery chains forlorn” and “The Devil thought he

had me fast/But I thought I’d break his chains at last” connect the biblical exodus

narrative with the reality of enslavement. These verses translated the story of

exodus, made it relevant to slaves’ daily lives, and emphasized that “exodus”

was not a metaphor, but a guide; not a meditation on persecution of Israelites

in Egypt, but an evolving reality.

Three sets of lyrics contend for the

status of original lyrics of “Go Down, Moses.” In 1862, the white hymnologist and

publisher of evangelical hymnals (and famed builder of fine pianos) Horace

Waters arranged and published “Go Down, Moses” in Songs of the Contrabands. Waters published a large number of

contrabands’ songs, and considered “Go Down, Moses” the contrabands’ theme

song. Harriet Beecher Stowe recorded in 1863 a second collection of verses when

she heard contrabands singing “Go Down, Moses.” Stowe or another person

transcribed it. In 1880, Fisk University published yet another version of “Go

Down, Moses” in the hymnal Songs of the Jubilee

Singers, one that transformed lyrics sung by former slaves to formal, arranged

lyrics. The distinguished musician and

composer arranged “Go Down, Moses” for the Fisk Jubilee Singers and their songbook,

Theodore F. Seward. He based his verses on those sung by the first Fisk

students, all former slaves.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers toured the United

States and Europe to raise funds for Fisk University’s buildings and

educational programs. The concerts brought spirituals transcribed in Songs of the Jubilee Singers to large

audiences, who were hearing African American religious, folk, and coded protest

music for the first time. Fisk University, founded in Nashville six months

after the Civil War ended, needed the $20,000 the choir hoped to raise to erect

the first buildings on campus. Skeptics doubted the tour would reach its

planned destinations, let alone raise $20,000.

The original concert program included religious

music from white churches, as well as spirituals from Songs of the Jubilee Singers. The polished, harmonious arrangements

of spirituals sung by the former slaves followed European traditions. The music

arranger emphasized precision and finish. He aspired to present art, not a

shadow (or worse, a caricature) of “plantation song.” Seward created arrangements

familiar to white audiences, conforming to their expectations of concert music.

Contemporaneous music critics noted “[The Jubilee Singers] have become familiar

with much of our best and sacred classical music, and this has modified their

manner of execution.”[10]

The choir performed in tailored, formal dress, as expected by audiences. Fisk

University did not have many funds, and the former slaves could not contribute

financially to purchase a formal concert attire. This demonstrates the choir’s assumption

that adhering as closely as possible to dominant culture norms was a necessity

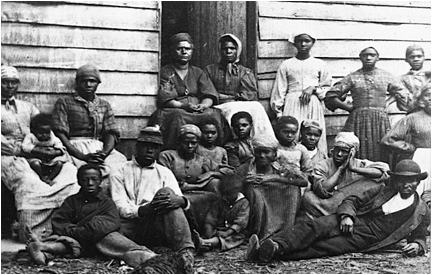

(see fig. 1).

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Fisk University Archive, Special Collections; Nashville, Tennessee; circa

1870s; <http://www.fisk.edu/academics/Library/SpecialCollections.aspx>. |

The spirituals from Songs of the Jubilee Singers were wildly popular, more than their

counterparts from white church singing. The choir conductor adapted the concert

program accordingly, and in the end it consisted mainly of slave spirituals,

albeit performed in concert style. The tour proved a great success despite a

slow start and initial disappointments. By 1878, the group had brought to Fisk

University over $150,000. The tour introduced dozens of African American

spirituals to large (mostly white) audiences in the North and across Europe.

Lyrics performed by the Fisk Jubilee

Singers differ from the other two earlier sets of lyrics, the contraband lyrics

transcribed by Horace Waters and the contraband lyrics transcribed by Harriet

Beecher Stowe. The contraband lyrics recorded by Stowe closely represent “Go

Down, Moses” as sung by slaves and fugitives. Horace Waters in Songs of the Contrabands and Theodore

Seward in Fisk University’s Songs of the Jubilee

Singers arranged “Go Down, Moses” for concerts and formal choirs. Waters’

version faithfully followed the literal narrative of the biblical exodus, whereas

Seward transcribed lyrical improvisations and innovations as well. Seward’s

version contains all but one of the lyrics of the contrabands recorded by Stowe.

Since almost all singers in the

Fisk Jubilee Singers had been slaves, the Fisk University songbook best

reproduces the lyrics originally sung by slaves. No two live renditions of “Go

Down, Moses” used the same set of lyrics, since calls arose organically and

spontaneously from the congregation; no two versions of “Go Down, Moses” sung

by groups of former slaves contained the same set of calls. Only one lyric in Horace

Water’s contraband version does not appear Seward’s Songs of the Jubilee Singers: “He sits in the heaven and answers

prayers.”

The version of “Go Down, Moses” published

by Horace Waters in 1862 may have influenced the 1880 Fisk University

transcription; the musicians at Fisk University knew Waters’ songbook. Waters’

transcription, while reflecting his own rhyming, choice of words, and

grammatical constructs, accurately incorporated the slave spiritual’s phrases.

Horace Waters’ version did not change the lyrics, other than to arrange them in

“proper” English with conventional rhyming and grammar.

Trying to reconcile the three sets of

lyrics for “Go Down, Moses” demonstrates the difficulty of discerning the original

lyrics of spirituals or any folk song. Folk songs have no author, but arise

from a community, and evolve with circumstances. They do not lend themselves to

standard European musical notation and standard American English pronunciation,

spelling, idiom, or grammar. The sheer difficulty of indicating the notes,

intervals, melody, and style of spirituals using classical European music

notation stymied transcribers. The collector—whether white or

black—imposed his or her memory, taste, and preferences on the

transcription, limited by his or her strength, or weakness, in transcribing

music.

Go Down, Moses: Musical

Analysis

“Go Down, Moses” is a majestic,

commanding song, sung slowly, almost ponderously. Its minor key and flattened

intervals lend it a plaintive, haunting air. The embedded response “Let my

people go” in each verse comes in at a low pitch, the same low pitch that

begins each verse. But the

response “Let my people go” does not climb the register, as does the call that

precedes it. The pitch stays low and the music pounds out slowly and

deliberately the words “Let my people go.” The call and response start on the

same note, but the response resolves the two-line phrase, lending an air of

finality to the command, “Let my people go.”

The chorus enters on a higher note than the

verse it follows. This gives it a thrust of energy and urgency that matches the

sentiment of the chorus: the command to Moses to free the captives. The final

phrase of the chorus, another repetition of “Let my people go,” is musically

identical with “Let my people go” as sung in a verse. The immobility of the

music matches the implacable nature of God’s command. Each line of each verse

ends with those three implacable notes, a rising C—D-flat—E-flat;

the chorus’ ending again repeats the same three implacable notes. The overall

effect is one of awe and power. The music itself commands.

Singers slowed and exaggerated the steady

and regular rhythm that contained slight internal syncopation, to place even

greater emphasis on “Let my people go.” That phrase resolves the two call-and-response

couplets of each verse, each repetition of the chorus, and resolves “Go Down,

Moses.” Theodore Seward stated that the melodies “spring from the white heat of

religious fervor during some protracted meeting in a church or camp.” He remarks

on the complicated and “sometimes strikingly original” rhythm, and the preference

for using multiple meters (ways to measure time, or beat out time). Former

slaves accompanied rhythms and meters with “beating of the foot and the swaying

of the body.” Seward documents the use of a musical scale with the fourth and

seventh notes omitted, of the seven notes in a Western scale.[11]

[12]

He articulated for the first time these three prominent aspects of African

American musical innovations regarded today as the great contributions of

African American music: emphasis on rhythms, multiple meters, and the

pentatonic scale known as the “jazz scale” or “blues scale” that omits the

fourth and the seventh notes in the Western musical scale.

“Go Down, Moses”: Transmission

African Americans living under slavery created

the spiritual “Go Down, Moses” during

the period of the Underground Railroad. In the years preceding the Civil War, slaves

escaped by following explicit pathways, traveling from staging house to staging

house. Tradition holds that Harriet Tubman inspired “Go Down, Moses.” As a (singing)

conductor on the Underground Railroad, Tubman led hundreds of slaves to freedom.

Escaping slaves called her Black Moses, or simply Moses. “Go Down, Moses” acted

both as metaphor and literal expression of the Underground Railroad: people

traveling the Underground Railroad made a literal journey to freedom with the

help of their Moses. Harriet Tubman, a powerful singer and storyteller (and a

fierce, determined, brilliant and imposing figure) dramatized stories to bring

them to life. Photographs attest to her powerful presence (see fig. 2, pg. 20).

Tubman’s legend preceded her in life and even more so surrounds her since her

death. One anecdote from Tubman’s life stories shows how she used the power of

music to escape detection:

At another time she was being questioned

by men on a train who were looking for her and she said: “Gentlemen, let me

sing for you”—she had a great voice for song—then sang on for mile

after mile till they came to the next station, then bade them good-bye and left

the stage.[13]

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Harriet

Tubman. Accessible Archives, <http://accessiblearchives.com>. |

Spirituals signaled the presence of

conductors or slaves on the Underground Railroad, acted as a beacon for a station,

informed slaves of the near presence of Harriet Tubman, acted as communication among

conductors and slaves and—the overriding use of spirituals—expressed

and provided the storyline to follow (exodus), and provided succor to those

making the journey. The spiritual expressed the thought of freedom ahead, urging

singers and listeners to persevere individually and communally, and thus

achieve victory.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, abolitionist and

author of the controversial “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” collaborated with a group of tens

of thousands of women in the United Kingdom, who signed a petition calling for

their sisters in the United States to battle slavery. Stowe’s thirteen-page

reply to their petition, printed in The

Atlantic magazine in January 1863, included an account of contrabands singing

traditional spirituals for President Lincoln and assembled politicians; their

rendition of “Go Down, Moses” moved Stowe deeply. Stowe printed the

contrabands’ lyrics to “Go Down, Moses” in full in her letter to the women of

the United Kingdom. A fragment of the letter reads:

This very day the

writer of this has been present at a solemn religious festival in the national

capital, given at the home of a portion of those fugitive slaves who have fled

to our lines for protection—who, under the shadow of our flag, find

sympathy and succor. The national day of thanksgiving was there kept by over a

thousand redeemed slaves, and for whom Christian charity had spread an ample

repast.

Our Sisters, we wish you could have

witnessed the scene. We wish you could have heard the prayer of a blind old negro,

called among his fellows John the Baptist, when in touching broken English he

poured forth his thanksgivings. We wish you could have heard the sound of that strange rhythmical chant which is now forbidden

to be sung on Southern plantations – the psalm of this modern

Exodus—which combines the barbaric fire of the Marseillaise with the

religious fervor of the old Hebrew prophet.

Oh, go down,

Moses, Way down into Egypt’s land!

Tell King Pharaoh

to let my people go!

Stand away dere, Stand

away dere,

And let my people

go!

Oh

Pharaoh said he would go ‘cross!

Let

my people go!

Oh,

Pharaoh and his hosts were lost!

Let

my people go!

You

may hinder me here, but you can’t up dere,

Let

my people go!

Oh,

Moses stretch your hand across!

Let

my people go!

And

don’t get lost in de wilderness!

Let

my people go!

He

sits in de heavens and answers prayers.

Let

my people go!

As we were leaving,

an aged woman came and lifted up her hands in blessing. “Bressed be de Lord dat

brought me to see dis first happy day of my life! Bressed be de Lord!” [emphasis

mine]

In all England is

there no Amen?[14]

Harriet Beecher Stowe implored her

sisters in England to champion for a second time the cause of emancipation, as significant

numbers of people in the United Kingdom favored letting the South go—that is, grant the South

secession and independence, and continue the practice of slavery. Stowe chose

“Go Down, Moses” to amplify her appeal. She included a relatively long list of

lyrics to bring to life for her readers in England the heartfelt appeal behind

the emotional poetry that described the contemporaneous exodus. Stowe asked her

sisters across the Atlantic to hear the prayer of the former slave—Blessed

be the Lord that brought me to see this first happy day of my life! Blessed be the

Lord!—and to add their amen. The music of “Go Down, Moses” transcended

the camp and the woods and the plantation, and became part of political

discourse among influential bodies of women on both sides of the Atlantic. The Queen

of England may have known the spiritual “Go Down, Moses” due to this collaboration

of abolitionist women in the United Kingdom and Harriet Beecher Stowe; the

Queen specifically requested the Fisk University choir sing it for her in a

special performance during their European tour in the early 1880s.

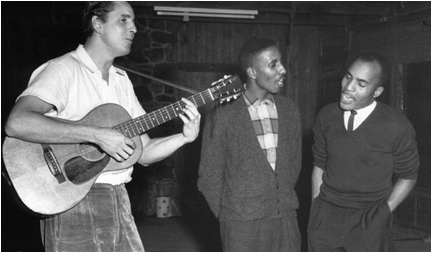

The man Harriet Beecher Stowe heard

singing “Go Down, Moses” lived in the Grand Contraband Camp in Virginia. In

1862, the camp housed several thousand escaped slaves. The contrabands included

men, women and children, clothed and housed by the Union army (see fig. 3, pg.

24). Sheet music and lyrics published in the North attest to the popularity of

contraband music, much in fashion. On September 7, 1861, a visitor to the

Contraband Camp reported:

I passed around

the fortress chapel and adjacent yard where most of the “contraband” tents are

spread. There were hundreds of men of all ages scattered around. In one tent

they were singing in order, one man leading as extemporaneous chorister, while

some ten or twelve others joined in the chorus. The hymn was long and plaintive

as usual and the air was one of the sweetest minors I ever listened to.[15]

|

|

Fig. 3. Exodus:

“Contrabands,” fugitive slaves emancipated upon reaching Union-controlled territory,

sit outside a house, possibly in Freedman’s Village in Arlington, Virginia, in

the mid-1860s. Photo and caption: Aurora Mendelsohn,

“From

the Civil War to Our Seders, A Song of Redemption,” The Jewish Daily Forward, <http://forward.com>.

|

Another account

comes from a New England minister, George H. Hepworth, who attended a church

service in Louisiana. A large number of escaped refugees, not yet freed, had

gathered “from a radius of forty miles, and formed themselves into colonies

with from one to five hundred in each; and were living on three-quarters

Government rations, and working in every which way in which they could.” He

joined about one hundred gathered in a rough shack for a church service:

For

a few moments, perfect silence prevailed … At length, however, a single voice,

coming from a dark corner of the room, began a low, mournful chant, in which

the whole assemblage joined by degrees. It was a strange song, with seemingly

very little rhythm, and was what is termed in music a minor; it was not a

psalm, nor a real song, as we understand these words; for there was nothing

that approached the jubilant in it. It seemed more like a wail, a mournful,

dirge-like expression of sorrow.

At

first, I was inclined to laugh, it was so far from what I had been accustomed

to call music; then I felt uncomfortable, as though I could not endure it, and

half rose to leave the room; and at last, as the weird chorus rose a little

above, and then fell a little below, the key-note, I was overcome by the real

sadness and depression of soul which it seemed to symbolize …

They

sang for a full half-hour. – an old man knelt down to pray. His voice was

at first low and indistinct … He seemed to gain impulse as he went on, and

pretty soon burst out with an “O good, dear Lord! We pray for de cullered

people. Thou knows well ‘nuff what we’se been through: do, do, oh! do, gib us

free!” when the whole audience swayed back and forward in their seats, and

uttered in perfect harmony a sound like that caused by prolonging the letter

“m” with the lips closed. One or two began this wild, mournful chorus; and in

an instant all joined in, and the sound swelled upwards and downwards like

waves of the sea.[16]

As a cultural force, the music of the

contrabands wrought deeper and more personal connections among people of the North

and former slaves. Other accounts of the contraband camps relate that music was

ever present, particularly “plaintive hymns.” No visitor to the camps failed to remark in emotional detail

the effect of the music. Michel Fabre, a Professor

at the Research Center in African-American Studies at the University of Paris

III, wrote, “The presence of the fugitives [contrabands] in the Union

army provided a sort of transition towards human and cultural understanding of

a people whose artistic productions had not been acknowledged by the South.”

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote of the fugitives, who served in the Union army, that “perhaps

for the first time, the north met the Negro slave face to face and heart to

heart with no third witness.”[17]

When President Lincoln read aloud the

Declaration of Emancipation on January 1, 1863, congregations of freedmen and

slaves celebrated in song. “Black men assembled in ‘rejoicing meetings’ all

over the land on the last night of December in 1862, waiting for the stroke of

midnight to bring freedom to those slaves in the secessionist states.”[18]

At the contraband camp in Virginia, people sang “Go Down, Moses” over and over.

A “sister broke out in the following strain, which was heartily joined in by

the vast assembly”:

Go Down, Abraham,

Away down in Dixie’s land;

Tell Jeff Davis

To let my people go.”[19]

Singers always improvised African American folk song and

spirituals to add lyrics that described contemporaneous struggles, political

leaders, grassroots leaders, and events. Freedmen celebrated Abraham Lincoln in

the role of Moses and cast Jeff Davis, President of the Confederacy, as Pharoah,

in this early example of new lyrics spontaneously added to an old spiritual.

“Go Down, Moses” in the Civil

Rights Movement: “Go Tell It on the

Mountain”

The phrase most associated with “Go Down,

Moses”—“Let my people go”—entered the civil rights freedom song “Go

Tell It on the Mountain.” The theme of exodus continued to resonate during Jim

Crow. When Fannie Lou Hamer replaced the last line of the Christmas hymn “Go

Tell It on the Mountain” with the phrase “Let my people go,” she transformed the

upbeat, fast-tempo Christmas song into a song of exodus. The original lyrics

Go tell it on the mountain,

Over the hills and everywhere,

Go tell it on the mountain,

That

Jesus Christ is born.

became

Go tell it on the mountain,

Over the hills and everywhere,

Go tell it on the mountain,

To

let my people go. [emphasis

mine]

John Wesley Work, Jr., Professor of

Latin, Greek History and Music at Fisk University, first collected, adapted and

published “Go Tell it on the Mountain” in his 1915 songbook, Folk Song of the American Negro.[20]

Work’s lyrics of the Christmas hymn include “While shepherds kept their watching/O’er

silent flocks by night/Behold throughout the heavens/There shone a holy light”

and “Down in a lowly manger/The humble Christ was born/And God sent us

salvation/That blessŹd Christmas morn.” The freedom song lyrics bear no

resemblance to the Christmas hymn.

“Go Tell It on the Mountain” is simpler than

“Go Down, Moses,” with short narratives or, in some instances, lacking a story

line, with powerful verses that stand alone. It lent itself to lining out and

congregational improvisation.[21]

Members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party sang these lyrics at the

1964 Democratic Convention:

Verse

Who’s that yonder dressed in red? [variation

on the Christmas hymn’s

Let my people go. “Who’s that dressed in white?”]

Must be the children Bob Moses led

Let my people go. [Bob Moses was a civil rights leader

and SNCC Field Secretary.]

Chorus

Go tell it on the mountain

Over the hills and everywhere

Go tell it on the mountain

To let my people go.

Verse

2

Who’s that yonder dressed in black …

Must be Uncle Tom’s turning back …

Verse

3

Who’s that yonder dressed in blue …

Must be registrar’s coming through …

Improvisers rewrote entire verses of the Christmas hymn,

such as

You know I would

not be Governor Wallace

I'll tell you the reason why,

I'd be afraid my Lord might call me

And I would not be ready to die.[22]

With the transformation of the last lyric from “Jesus Christ

is born” to “Let my people go,” “Go

Tell It on the Mountain” became an exodus-themed freedom song, although it

continued as a Christmas hymn in churches and religious gatherings.

The civil rights leader and voting rights

activist Fannie Lou Hamer named “Go Tell It on the Mountain” one of her two

favorite protest songs. Accounts of Hamer’s life describe how strongly she

identified with “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” She loved and sang this song at

almost every action, and often led with it. Fellow activists called “Go Tell It

on the Mountain” her signature song, along with “This Little Light of Mine.”

Hamer joined the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee in 1962 after attending a meeting in Ruleville,

Mississippi, where SNCC Field Secretary James Bevel taught the impoverished African

American community how to register to vote. SNCC staff throughout Mississippi—the

state considered the “iceberg” of opposition to equal rights—taught people

in workshops how to register, and how to teach others to register, in a climate

of brutal violence. The disenfranchised sharecroppers lived in near-destitution

under the harshest conditions of Jim Crow, often referring to the land they

worked as the “plantation.” African Americans who registered to vote in

Mississippi often lost their employment and housing. Incensed landowners turned

sharecroppers off the land their families had worked for generations. The day Hamer

registered to vote, she lost her home, and the right to farm the land her

family had worked since the days of slavery. Ten days later, people who saw Hamer’s

actions as a dangerous affront drove by the house where she slept, and pumped

bullets into the house. Fortunately, no one was hurt. A year later, local

police arrested Hamer and others, and forced two African American men also under

arrest to beat her brutally with a blackjack; she suffered for the rest of her

life from injuries sustained that day. (She described her beating, and the

screams she heard from adjacent cells, during her televised testimony at the

1964 Democratic Convention, shocking the nation.) Rarely in United States

history have citizens paid more dearly to exercise a civic duty. Fannie Lou Hamer

said:

Everything [James

Bevel] said [at the 1962 church meeting, where Hamer first heard SNCC workers

address her local community], you know, made sense. And also, Jim Foreman was there. So when they stopped

talking, well, they wanted to know, who would go down to register you see, on

this particular Friday, and I held up my hand …

The thirty-first

of August in ’62, the day I went into the courthouse to register, well, after

I’d gotten back home, this man that I had worked for as a timekeeper and

sharecropper for eighteen years [from ages 29-47], he said that I would just

have to leave … So I told him I was wasn’t trying to register for him, I was

trying to register for myself … I didn’t have no other choice because for one

time I wanted things to be different.[23]

Singing rewritten

spirituals like “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and “This Little Light Of Mine” lit

up the face and soul of Fannie Lou Hamer. Her determined enthusiasm emboldened

all who were with her. Hamer refused to back down. When the historian Howard Zinn

asked her if she would remain with the movement despite beatings and attacks on

her life, she replied with the words to a spiritual: “I told them ‘if they ever

miss me [from the movement] and couldn’t find me nowhere, come on over to the

graveyard, and I’ll be buried there.’ ”[24]

Like African Americans in the days of slavery, and Africans before them, Hamer

chose song to express her deepest emotions. Zinn said, “when [Fannie Lou] sings

she is crying out to the heavens.”

Like

other songleaders in the movement, Hamer had known the spirituals since

childhood:

Her mother had sung children’s songs to

her when she was little. Her church taught her its hymns and its spirituals.

Her life often gave her nothing but time in which to sing them—time in

the fields, time at the ironing board, time fishing along the rivers and

bayous. And later, time on marches, even time in jail. Her allies in the civil

rights movement taught her their songs, and she became the unofficial song

leader almost wherever she went. At training sessions, her robust voice and

emphatic presence carried people with her in song, bringing together those who

had been strangers, making them comfortable enough to talk easily.[25]

Hamer wove the music of the spirituals

with her political leadership. Leaders in the Democratic Party were not ready

to fight for African Americans’ full participation in the political process, despite

extending limited political, legal and law enforcement support to the movement.

In Mississippi in 1964, the Democratic Party denied African Americans fair representation

at the national convention to choose a presidential candidate. In reaction, Hamer

and other activists

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Fannie Lou Hamer,

center, singing at Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party boardwalk rally. From

left: Emory Harris, Stokley Carmichael (Kwame Ture) in hat, Sam Block,

Eleanor Holmes, Ella Baker. Civil Rights Movement Veterans,

<http://crmvet.org>. |

organized the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and

traveled by bus to participate in the convention. They demanded to be seated as

representatives of the Democratic Party from Mississippi. The Credentials

Committee fought back and a “compromise” was forced; the Democratic Party

granted the MFDP a mere two seats. Hamer and the MFDP rejected the compromise.

Her stirring speech on national TV that detailed her own brutal beatings and what

she endured in the struggle, and that included implacable, now-famous statement

“I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired” have entered national

consciousness. Televised nationally leading a powerful rendition of “This

Little Light of Mine,” Hamer reached millions of United States citizens with

her song, as no reports of political infighting at the Democratic National

Convention could. “When Mrs. Hamer finishes singing a few freedom songs one is

aware that he has truly heard a fine political speech, stripped of the usual

rhetoric and filled with the anger and determination of the civil rights

movement … on the other hand in her speeches there is the constant thunder and

drive of the music,” a folk singer and fellow participant in the 1964 Mississippi

Freedom Summer observed.[26]

Fannie Lou Hamer and other activists at the convention sang freedom songs daily

outside the convention hall to draw attention to their presence and to express

their demands (see fig. 4, pg. 32).

Although a sharecropper who worked in the

fields since early childhood and one of eleven children in a desperately poor family,

Fannie Lou Hamer spoke powerfully “with the constant thunder and drive of

music” before audiences of thousands, with historically and politically astute

analyses of American society. As vital and influential as charismatic preachers

and songleaders in the black church, Hamer joined forces later with protestors

in the anti-war movement. She carried her passion and song to other

movements for social justice: the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County and

Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Poor People's Campaign.[27]

The

nineteenth-century spiritual “Go Down, Moses,” and the twentieth-century freedom

song linked with it, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” worked in their respective

eras to encourage and energize African Americans seeking freedom and full

rights. Both spirituals also acted as organizing tools, sung by powerful songleaders.

Congregations continue to sing “Go Down, Moses” and “Go Tell It on the

Mountain” in churches in diverse ethnic communities, including but not limited

to African American and white churches. “Go Down, Moses” is the first song in many

American Haggadahs, the text and music that are recited and sung at the Jewish

celebration of the biblical exodus, the Passover. Songs demanding freedom

helped African American protestors articulate demands, and helped communities work

together to fight for freedom.

Chapter 2:

Perseverance—“We Shall Not Be Moved”

The march was stopped about a block and a

half from the campus by forty city, county and state policemen with tear gas

grenades, billy sticks and a fire truck. When ordered to return to the campus or

be beaten back, the students, confronted individually by the police, chose not

to move and quietly began singing “We Shall Not Be Moved.”[28]

Labor and civil rights activists sang “We Shall Not Be

Moved,” a well-known spiritual turned protest song, to build community and to help

people persevere and struggle together. It originated as an African American

spiritual in the nineteenth century or earlier. Zilphia Horton, music director

at an adult education center named Highlander Folk School, learned it from 1930s

labor union singers, and incorporated it into the Highlander repertoire of

protest music. As part of the Highlander repertoire, it moved to the civil

rights movement when Guy Carawan, music director at Highlander Folk School in the

late fifties and early sixties, taught it to student activists. People in the

labor and civil rights movements sang it in protests, continually improvising

the lyrics. Its melody did not change significantly over time, but tempo,

rhythm, and lyrics did. Contemporaries considered it the anthem of the labor

movement.

Other perseverance-themed spirituals

later used as protest songs include “Come and Go With Me To That Land,” “We’ll

Never Turn Back (We’ve Been ‘Buked and We’ve Been Scorned),” “Come By Here

(Kumbaya),” “Sing till the Power of the Lord Come Down,” “Get On Board, Little

Children,” “I Ain’t A-Scared of Your Jail,” “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and

“We Shall All Be Free.” Posterity does not record all songs active in the labor

and civil rights movements. The historian John Greenway notes that a large

class of protest songs “some of which are unapproached for bitterness, anger,

vehemence, and sincerity” are not included in his study as he considered them

“unprintable” (presumably for profane or offensive lyrics).[29]

Standards of profanity loosened over the decades. While he does reprint the

lyrics, “You low-life trifling bastard, You low-life thieving snitch; You

selfish, greedy, bastardly thief, You God-damned son of a bitch,” he goes on to

comment “that’s about as far as it can be carried.”

Folk songs that doubled as protest songs

invariably originated as religious songs and slowly introduced secular elements

that described the day-to-day earthly struggle for justice, in addition to a yearning

for divine deliverance. The twelfth-century writer William of Malmesbury

recounts “his ancient predecessor, Aldhelm” sang religious ditties until he

gained listeners’ attention. He could then insert secular ideas into the songs

and keep listeners’ attention; otherwise, people would have not stopped and heeded

Aldhelm’s protest songs.[30]

Integrating protest music with struggle dates to time immemorial (especially

religious music), but strained and polemical music predominated in the 1930s-1950s

white labor movement.

“We Shall Not Be Moved”:

Origins

Pete Seeger hypothesized “I Shall Not Be

Moved,” the predecessor to “We Shall Not Be Moved,” was created before 1860. It

appeared in print in 1908, copyrighted by the Rodeheaver Company. A musician

and composer, Alfred H. Ackley (1887-1960), was interviewed by the magazine “Defenders

of the Christian Faith” in 1941. He stated that he composed “I Shall Not Be

Moved” in 1906 and created the central lyric “Like a tree planted by the

water.” While this is possible, it is also possible he transcribed a common

spiritual, adding his own stamp.

“We Shall Not Be Moved”:

Lyrical and Musical Analysis

The Bible verse Jeremiah 17:7-8 supplies

the central form and meaning of “We Shall Not Be Moved”:

Blessed is the man that trusteth in the

Lord for he shall be as a tree planted by the waters, and that spreadeth out

her roots by the river ...

The standard first verse in traditional religious, labor,

civil rights, and contemporary collections does not vary:

We shall not, we

shall not be moved

We shall not, we

shall not be moved

Just like a tree

that’s planted by the water

We shall not be

moved.

The spiritual “We Shall Not Be Moved” expresses determination

in the face of adversity. This message defiantly contradicts the assumption

that African Americans passively accepted their status defined by the dominant

culture. The spiritual embodies perseverance by individuals and communities. People

singing the courageous lyric “Like a tree, I won’t be moved—We won’t be

moved” confronted violence on the picket line in 1938, and in the South in the

1960s. They refused to be deterred. Singing the spiritual emphasized their group

solidarity, and willingness to persevere together.

Subsequent verses elaborate motivations

for their determination. “We are fighting for our freedom,” a verse common to

the labor and civil rights movements, provides one reason why “we shall not be

moved.”

We’re fighting for our freedom, we shall

not be moved

We’re fighting for our freedom, we shall

not be moved

Just like a tree that’s planted by the

water,

We shall not be moved.

Improvisation transformed the spiritual into a ballad describing

a current dispute. Members of the West Virginia Miners’ Union sang “We Shall

Not Be Moved” as a protest song in 1931 during a strike, an early documented usage.[31]

The first verse began a song-ballad about the strike, and started by describing

the union leader: “Frank Keeney is our captain, we shall not be moved.”

Verse 1

Frank Keeney is our captain, we shall not be moved

Frank Keeney is our captain, we shall not be moved

Just like a tree that’s planted by the water

We shall not be moved.

Verse 2

Mr. Lucas has his scabs and thugs …

Verse 3

Keeney got our houses bonded … [32]

Songleaders easily lined out a narrative

due to the song’s simple form, and the brevity of each verse. A songleader, or

any member of a group, called out a first line; the group repeated it, and then

sang the remaining three lines. The central lyric and central image—“just

like a tree that’s planted by the water”—did not change as the spiritual

moved from church to picket line, but appeared as the third line in each verse.

Protestors by their actions mirrored the image of

“a tree that’s planted by the water.”

The lyrics of “We Shall Not Be Moved” differ

radically in the church, labor, and civil rights versions. Strikers at the

Rockwood Tennessee hosiery plant in 1938 created the first five improvisations

used in the labor movement that stand on their own (that is, do not form a narrative).[33]

They refer plainly to work stoppages and violence on the picket line; they are

not the abstract images of a religious hymn. The next lyrics introduced during

the labor movement belong to a 1940 narrative version. Union members rallied

behind the strong president of the C.I.O, John L. Lewis, and sang, “You can

tell the henchmen, run and tell the superintendant” that John Lewis led and

protected them. The declaration of determination remains the same, “We shall

not be moved, like a tree planted by the water.”

Singers in the civil rights movement

focused less on specific actions and leaders than during the labor movement.

New improvisations emphasized the goal—freedom. Versions of “We Shall Not

Be Moved” from the 1950s-1960s did incorporate one important lyric found in all

transcriptions of the labor movement’s version, “We are fighting for our

freedom.”

“We Shall Not Be Moved”: Transmission

“We Shall Not Be Moved” became so integral

to the labor struggle that its roots as a spiritual came as a surprise to some,

who assumed it was composed for the labor movement. Members of segregated labor

unions, often bigoted and unwilling to march with their African American

brothers and sisters, would have been shocked to learn they were shouting out

African American songs. (The term “brothers and sisters” was used in the labor

movement as well as during the civil rights movement, and in African American culture

through today). Joe Glazer, “Labor’s Troubadour,” lifelong activist, songleader,

union organizer and Education Director of the United Rubber Workers, AFL-CIO,

wrote in his memoir:

Remember, these workers were from small

mill towns and probably strict segregationists, followers of the likes of

George Wallace and Jesse Helms. For them it was a union song, sung in a union

hall. I was teaching [Negro spirituals] to white textile workers all over the South.[34]

Glazer emphasized that not even activists

in the labor movement realized that the power of “We Shall Not Be Moved”

derived from the power of the spirituals. “We Shall Not Be Moved” was sung at almost

all union conventions and on the picket line, sometimes for hours on end, as

reported by Joe Glazer, who led songs at thousands of meetings, conventions and

strikes:

Next to

“Solidarity Forever,” “We Shall Not Be Moved” is the best known and most widely

sung labor song in the United States and Canada. Whenever union songs are

heard, it is a must.

At convention

hotels in the wee hours of the morning, enthusiastic union delegations have

been heard singing “We Shall Not Be Moved” with great gusto, and, despite the

determination expressed in the song, they have on occasion found themselves

definitely “moved”—by hotel police.

The song is a

great favorite on picket lines because it is easy to add dozens of verses telling

the story of any particular strike. At one strike meeting in Biddeford, Maine,

in 1945, several thousand textile workers roared it out, adding new verses

continuously for a solid half hour.[35]

Zilphia Horton led protesters in singing

“We Shall Not Be Moved” during a 1945 strike in the rural South: a strike of

the South Carolina CIO Food and Tobacco Workers Union in Daisy, Tennessee:

We were marching two-by-two with the

children in the band. They marched past the mill and four hundred machine gun

bullets were fired into the midst of the group. A woman on the right of me was

shot in the leg, and one on the left was shot in the ankle … Well, in about

five minutes a few of us stood up at the mill gates and sang, “We shall not be

moved, just like a tree planted by water …” and in ten minutes the marchers

began to come out again from behind barns and garages and little stores that

were around through the small town. And they stood there and WERE NOT MOVED and

sang. And that’s what won their organization.[36]

Although the American labor movement

incorporated song from its earliest days in the nineteenth century, and early

songbooks like those of the Industrial Workers of the World were widely known

and distributed, labor union meetings in the 1940s did not typically open and

close with music, and music did not permeate meetings. Unionists sang

infrequently, except in times of conflict. African Americans who attended early

labor meetings remarked on this difference. They were surprised the union

leader stood up, called the meeting to order, and commenced addressing agenda

items, rather than leading with a series of songs. Joe Glazer drew these

conclusions in the early 1950s about the use of music in the labor movement:

1. 99% of American industrial workers do not

sing labor protest songs except during strikes.

2. Rural workers are by far the most

productive in the matter of union songs and songs of social and economic

protest.

3.

Most

songs of this nature come from the rural South.

4. Labor protest songs, except the very

simple and the very good ones, have no chance to become traditional.[37]

While Glazer’s statement that 99% of workers sang only during

strikes is certainly a rhetorical flourish, and not based on statistical

analysis, Glazer had a unique perspective on the reality of the labor union

organizing. Glazer was the foremost songleader among union organizers and

activists, expressly hired in 1940 to travel to union organizing events,

conventions, and picket lines, to teach and lead protest songs.

Music was undeniably a significant force

during strikes even if the labor protest songs were not often sung in other

contexts. Additionally, labor movement historians document the use and purpose of

protest music in the movement, from the nineteenth century through today. Union

organizers understood that a protest movement needed to be colorful and

attractive to recruit and keep members. In 1941, a commentator on workers’

education wrote:

If labor is to stand up to fascism and

throw its strength in a final conflict for, rather than against, democracy … it

has to be equally colorful, attractive, compelling in its mass appeal [as mass

movements created by dictators]. Union bands, orchestras and choruses are

helping to generate this color and life. Yet labor music, in the sense of

original music written by or for workers, is a rich field almost untouched …

Mrs. Horton at Highlander Folk School conducts classes in song-leading. The

students’ interest, she says, “seemed to be based on the growing realization of

the need for group singing at meetings and consequently the need for [song]leaders.”[38]

Zilphia Horton described the power of music in the labor

action: leading strikers in singing “We Shall Not Be Moved” brought people out

of hiding, after being fired upon with machine guns, and gave them courage to

stand their ground. She concludes that this action, enabled and empowered by

the labor movement anthem, accounts for the strike’s eventual success. Singing

“We Shall Not Be Moved” strengthened community resolve and united protesters,

and in the words of the songleader and political leader, Zilphia Horton, won the

battle.

Tom Tippett in his 1931 history When Southern Labor Stirs eloquently

states the necessity of involving cultural elements in union organizing. When

peoples’ need for social and cultural ties among themselves are not met by the

union, they turn to organizations that provide those ties—including even

the Ku Klux Klan.

There are

educational, political and recreational movements through which all workers

function, and if their union does not maintain these activities, the trade-unionists

find them elsewhere, and they split their loyalties and interest in so doing.

Many trade-unionists are more emotionally solidified to a lodge, the Ku Klux

Klan, the American Legion or some other similar organization than they are to

their trade union. This is so, by and large, because those organizations give

their members opportunity to take part in what they feel is an idealistic

movement designed to improve the world. Everybody has an idealist spark; what

he does with it depends on who fans it into flame.

The pity is that

the [predominantly white] American trade unions have no program to marshal the

native idealism of their membership into a social movement. The lack of this program is particularly felt by southern mill workers,

who are situated in such drab surroundings that they naturally crave a spiritual

outlet. They are therefore extremely religious, and many of them belong to highly

emotional sects.

In Marion [North

Carolina], as well as in all other strikes, there was an obvious similarity

between their trade union activity and that of the church, and when some speaker would discuss the union in

terms of an all inclusive social movement their enthusiasm knew no bounds.

They caught the idea too, although it was new to them, and expressed it in

terms of seeing light dawning over the mountain tops to make them free.[39] [emphasis mine]

Union leaders came to understand this, and 1930s southern rural

protests included cultural activities, especially music. This diminished in the

1940s.

Tippett summarized the conditions that led to the infamous fierce and bloody textile

workers’ strike in Marion, North Carolina

in 1929. In the North Carolina Blue Ridge Mountains, workers endured difficult

conditions: twelve-hour and longer shifts, extremely low wages, and night work.

Mill operators illegally forced underage children to work, and required

everyone to work past the end of their shifts with no overtime pay. The company

store fleeced workers. Inadequate housing provided no running water or sewers,

resulting in a great deal of sickness. No recreational facilities existed,

although churches abounded that helped people materially and emotionally. Local

police, state troopers, and the federal army brutally crushed the strike with

tear gas and gunshots. Scores of people were wounded, twenty-five seriously,

and at least six workers killed. Later, mills owners blacklisted the unionists.

Local officials and the state governor, who called in state and federal troops,

crushed a bloody decade of worker resistance. They “smothered the effective

strike with the strikers’ own blood.”[40]

The effects of the famous Marion strike radiated throughout the labor movement,

even though it failed to improve working conditions or wages. [41]

Much of the music used during labor

protests in the rural South in the 1930s derived from African American

spirituals. White mill workers churched in the same fashion as their African

American counterparts learned and chanted “re-written Negro spirituals” on

picket lines and at meetings. White workers comprised roughly ninety percent of

mill workers’ unions; most poor African Americans in the South worked as

sharecroppers, and not in the new industries. Tippett observed:

…[at the] picket lines at night with

their camp-fires burning, the women and men stationed there chanted re-written

Negro spirituals across the darkness to inspire faith and courage; the mass

meetings oftentimes in a downpour of rain, and the strikers singing. In those

early weeks of the strike the Marion cotton mill [in 1929] workers caught a

glimpse of something intangible, but something which they obviously and